The Lowdown

Tracklib is an online music store where you can purchase full songs that are cleared for sampling. That means you can cop sections of a track for use in your own productions. Unlike royalty-free loop and sample services like Loopmasters and Splice though, Tracklib requires you to pay for usage of the songs, which vary depending on the licence type and length of the sample. It’s a cool (and legitimate) idea for those wanting to make tunes that are sample-heavy, though the song library is still quite small. Certainly one to watch for beatmakers and remixers.

Video Review

First Impressions / Setting up

Think of Tracklib as a digital version of a corner record store or vinyl swap meet – you know, the type you go to when you want to go crate digging for undiscovered gems and obscure stuff. That’s mainly what you’ll find on here, minus the dust and allergies (admittedly part of what made crate digging a fun way to pass an entire weekend).

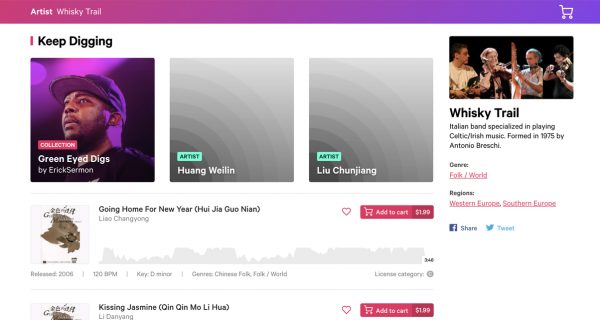

The site is intuitive and easy to use: Tracklib displays song collections, new tracks as well as popular releases. A “Discover More” portion helps you dig deeper through Tracklib’s collection of music.

What is sampling?

Sampling is the act of recording a portion of music for use in another. Sampling was used extensively in experimental music movements in the mid-20th century such as musique concrète, but gained prominence in the 70s when hip-hop and rap was born.

Those DJs and beatmakers used a sampler, which is basically a recorder that stored audio coming from an playback source like a turntable onto a storage medium such as tape, floppy disks and, later on, internal memory. Early samplers were expensive and had a steep learning curve.

You can do the same today easily and for next to nothing using your laptop, smartphone or tablet: fire up your DAW or production app, drop a song in and then chop up a portion of the music or specific drum hits. You can also connect a playback device like a turntable or CD player, record that into your DAW, and then do the chopping.

In Use

The way it works is you scour the Tracklib catalogue for a track you like. Once you’ve found a tune, you can purchase it (just US$1.99 per song) and then you can import it into your DAW for chopping up and sampling to your heart’s content. Though there are a few songs that give you full track stems (ie separate drum, bass, synth, vocal tracks) most of the songs come in a stereo master file (usually WAV format). This shouldn’t be a problem though, as tons of hip-hop and dance tracks were made exactly this same way for decades.

If you plan on releasing the song, you have to pay a licence fee ranging from US$50 up to US$2500, though most of the tracks are in the US$50 range. The artist of the song you sampled from then gets a royalty share of your revenue between 2 to 50% depending on how long the sample appears in your production.

The music on Tracklib are actual releases from artists – they’re not tracks made for music libraries, such as those used by music supervisors when they want to add music to a show or sites that licence music for YouTube videos. That means if you purchase a soul or Motown-esque track for instance, there’s a very high probability that you’re getting a tune that was made and released in the late 60s or early 70s as opposed to a modern production made to sound “vintage”, adding to the authenticity of your samples.

The only potential downside to this is that this keeps the catalogue small: Tracklib says that it’s adding over a thousand songs a week, making it a niche tool for producers. The good news is that it keeps the quality of the library rather high – I was able to find some odd funk gems with guitar lines that would make for great sampling and pitchshifting.

Conclusion

Tracklib is a cool idea, but it’s not for everyone. The main type of DJ/producer who will benefit from it the most will be beatmakers and hip-hop mixtape creators, although there is quite a bit of disco in here as well for some house and even techno sampling.

Where Tracklib excels is in its ease of licensing the music onboard as well its royalty scheme where the original artists are paid based on how long the sample appears on your production. While not cheap (you need to purchase a licence plus royalty-sharing based on sample length) it’s still easier (and potentially cheaper) than having to go through publishing agencies and record labels just to clear the samples used in your production. Definitely one to watch, and one to check out now if you’re making music in the hip-hop or house space.